The Associated Press State & Local Wire

July 9, 2000, Sunday, BC cycle; 12:07 PM Eastern Time

Come back to the five & dime, Margaret Mead, Margaret Mead

By MATT CRENSON, AP National Writer

TRAVERSE CITY, MI

A small man paces back and forth and chants into a metal stick.

He wears a black-and-white costume. A half a dozen similarly dressed minions scan the packed crowd as the chanting man’s voice intensifies. People in the crowd flash signals that drive the man’s chanting to an even greater frenzy.

Brian Hoey watches this spectacle from one side of the airless room, his back pressed against a cool cinderblock wall. What strange ritual is this? The black mass of a twisted cult? A warrior band’s preparations for battle?

No, it’s a real estate auction.

Gus and Barb Sharnowski have their 424-acre farm on the block, but Hoey isn’t here to bid. He’s an anthropologist. For him, the event offers an opportunity to delve into an almost unknown culture – the American middle class.

After dedicating their careers to studying exotic cultures in faraway lands, a few anthropologists are coming home. They’re taking research techniques they once used in African shantytowns and Himalayan villages to Knights of Columbus halls, corporate office buildings and suburban shopping centers.

The idea is to study American culture with fresh eyes unclouded by preconceived notions – to study “us” the way anthropologists used to look at “them.”

***

“I’ve seen a line coming out of that Dairy Queen that goes down the block,” Conrad Kottak says.

He’s cruising a Michigan suburb, pointing out cultural landmarks. The high school. A satellite dish. Fast food joints. Video rental stores. Newspaper boxes that indicate which residents are reading what.

Kottak, the chairman of the University of Michigan anthropology department, works with research fellow Lara Descartes on a project titled “The Relationship of Media to Work and Family Issues Among the Middle Class.” They interview people about their viewing habits, and spend evenings watching television in suburban homes.

After 38 years of research in Brazil, Kottak now finds himself pondering the mysterious allure of the Jerry Springer show.

“I think it’s very interesting,” he says.

He’s not kidding.

Traditionally, American anthropologists have been reluctant to study their own cultures. They’ve preferred remote subjects not yet gripped by Hollywood, pop music and the other tentacles of Western culture.

“They tend to study the exotic pre-industrial countries,” says Kathleen Christens, a program director for the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation in New York City.

Even when they do work in the United States, most anthropologists concentrate on subcultures: drug addicts, streetwalkers, transvestites.

***

Rebecca Upton, recently completed a classic anthropology Ph.D. in Botswana. There she studied the plight of infertile women in a society that values childbearing so strongly, a woman usually must have at least one child before a man will marry her. Now she does much of her research at an Ann Arbor playground.

Upton introduces herself to parents and interviews them about their lives for a project on young families that have just had or are considering a second child.

“There’s all this study about what happens at the first child,” Upton says. “There’s nothing about what happens with the second.”

Chatting with a mom on the local playground would seem easier than trying to understand the concerns of an infertile woman in southern Africa.

But it’s not.

In Africa, Upton could start from scratch, learning about the culture as if she were a child. In Ann Arbor, the first thing she has to do is forget everything she thought she knew.

“Suddenly I’m questioning my observations and assumptions about everything,” Upton says.

For example, she’s discovering that a second child often disrupts a family even more than the first did. Both parents can usually go back to work after the birth of their first child. But when the second comes along one parent, usually the mother, often has to put her career on hold.

She is considering changing her project’s long, academic title to “The Next One Changes Everything.”

***

“Something dramatic is happening here. Something is changing,” says University of Michigan anthropologist Tom Fricke.

America, he says, is going through the most profound social upheaval since the Industrial Revolution, when a rural nation of farmers became a country of factory towns and cities. Dual-career families, single parenthood and divorce are supplanting the traditional model of family. Factory work has given way to high-tech jobs that require college and graduate degrees. The mass media saturate our lives.

Everybody knows all this is happening, but there has been little research on how these changes affect the way Americans think about their lives.

To that end, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation has funded two research centers to do anthropological studies of the relationship between work and family life in middle-class America. Fricke heads the Center for the Ethnography of Everyday Life, based at the University of Michigan. The other one, based at Emory University in Atlanta, is called the Center for Myth and Ritual in American Life.

Anthropologists at the centers study American families the same way they would Polynesian cargo cults or Mongolian nomads – by inserting themselves into the daily lives of their subjects. So a few months out of the year, Fricke lives and works on a farm in Richardton, N.D., half way around the world from the Himalayan village where he has conducted most of his life’s work. Fricke occupies a spare bedroom in the home of Cal and Julie Hoff. They introduce him to friends and neighbors as “our anthropologist.”

The Hoffs’ 18 year-old son Casey would like to be a farmer too, but in a land of failing farms and dying towns, the prospects are bleak.

“You get this litany of despair out there,” Fricke says. “People are really leaving this part of the countryside.”

Fricke spends a lot of time in Richardton simply listening to people’s stories about life on the prairie. Later he plans to interview people who left town after high school to see how they relate to Richardton.

“If you move out at 18 you’re marked by that place,” Fricke says.

He pitches in on local farms, driving tractors, fixing machinery and stringing barbed wire. One day this spring, while tagging newborn calves, he nearly had his leg broken by an angry mother cow who repeatedly smashed him against a pickup truck.

Farm life is hardly alien to Fricke; he and his five brothers grew up in Bismarck, about an hour’s drive to the east. Now all six of them have scattered to distant cities in pursuit of their careers.

So it’s not hard to figure out how Fricke came up with the idea for his project, “Rural Parents & Urban Children; Place, Work, Migration, and the Natal Home.”

“I’ve always been studying myself,” Fricke says. “Even in Nepal.”

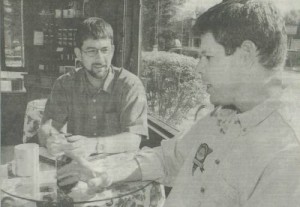

Brian Hoey, left, a doctoral student at U-M, interviews Mike Busley, owner of the Grand Traverse Pie Company of Traverse City. Hoey is among a group of students studying the American middle class. (AP Photo)

Hoey has taken it a step further – he has practically gone native. In December he moved to Traverse City, a town of 15,000 nestled into a bay of Lake Michigan. His research project – to study people who have recently moved to Traverse City.

In recent years, urbanites have flocked to Traverse City in search of a low-stress life. Hoey has met dozens of these middle-class refugees who sacrifice salary and first-run movies for a slower pace and natural beauty.

Everybody who moves to Traverse City seems to have a similar story. Take Mike Busley. He moved here from San Diego, where he worked as an engineer for General Dynamics. He made good money, but the projects he worked on kept getting axed. His division kept getting swallowed up or sold off. He was growing tired of the corporate jungle.

So on his 40th birthday, Busley quit his job, moved his family to Traverse City and opened the Grand Traverse Pie Company on Front Street.

“I had never baked a pie in my life,” Busley says.

He’s telling his tale in the coffee-shop part of his store, the smell of pies in the air and the jingle-bells on the door ringing whenever a customer walks in. Hoey sips a cup of decaf as he listens.

Busley explains how he got grocery stores in Detroit and Grand Rapids to sell his pies. He tells how quality ingredients and pie-baking excellence have twice won him top prize at the Best Cherry Pie in Northern Michigan competition. He grimaces when he reveals that folks around town call him “the pie guy.”

Busley tells an inspiring tale of how one man paved the way to paradise with pies.

But Hoey hears more than that. To Hoey, a Grand Traverse Pie Company pie is more than cherries and filling and crust. It is a powerful symbol in a tumultuous world, an edible icon of the good life.

Hoey tries to explain this all in complex academic jargon, then suddenly pauses and smiles.

“He’s selling an image,” Hoey says. “He’s selling a piece of the pie!”

Copyright© 2000, LEXIS-NEXIS, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All RightsReserved.